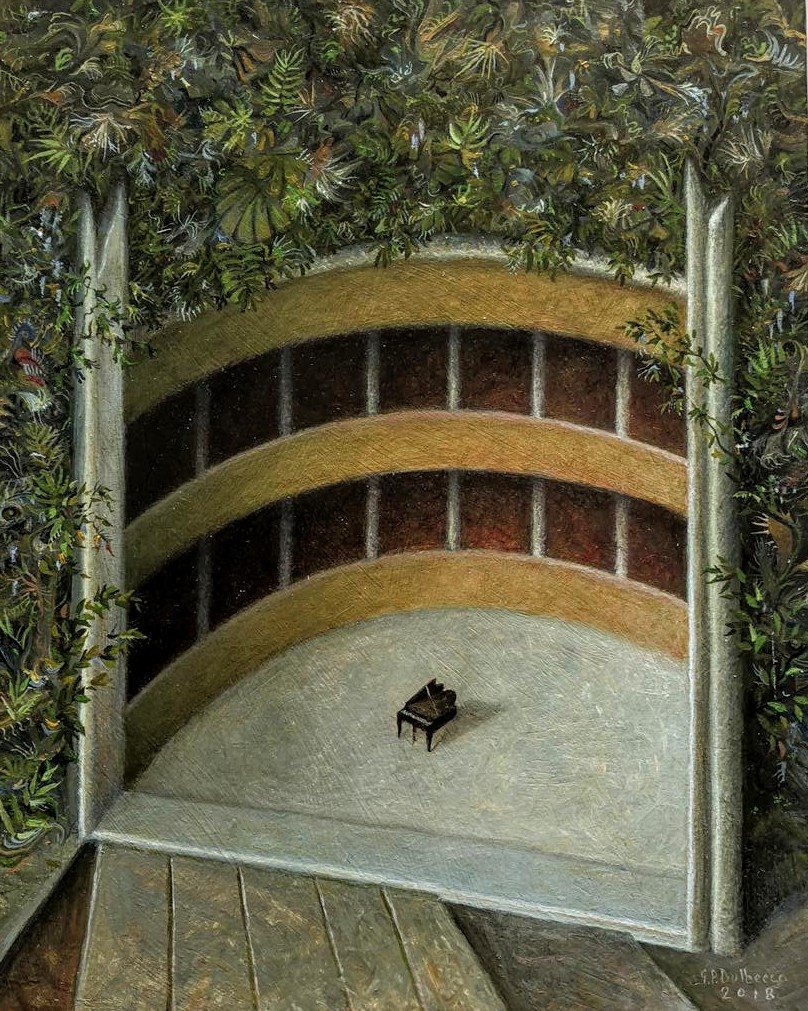

Gian Paolo Dulbecco © 2022

THE PROSE POEM & THE STARTLING IMAGE

by Amorak Huey

THE IMAGE—“the language of the particular,” as Mary Oliver calls it—is a cornerstone of poetry. Poems need images. (Yes, there are exceptions, there are always exceptions, there are no rules, write what you want, how you want, nothing I or anyone says about poetry is absolute, every craft essay about poetry should come with this caveat: what I offer here is a way of considering the poem, not the way. For the duration of this essay, I’m claiming that poems need images. Who knows how I will feel about it all tomorrow?)

By image, I don’t mean only “visual description.” I mean any language that appeals to any of the five senses. The word has its etymological roots in imagination.

Connected words and concepts, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, include semblance, hallucination, illusion, apparition, mental representation of a person or object, likeness, manifestation, death mask of an ancestor. What poem doesn’t need a death mask of an ancestor?

So much of what we’re trying to do when we write is evoke for the readers that mental representation: we want to render our subject in our reader’s consciousness: we want them to feel the emotion we’re chasing, see the landscape, hear the echo, smell the distant fires. We do this by appealing to the senses. Our work, as Mark Doty puts it in his book The Art of Description, is “to find accurate words . . . terms commensurate with the clamoring world.” Robert Pinsky says one of the defining characteristics of poetry is that its medium is the reader’s breath. He’s talking about the music of a poem; perhaps, when it comes to the image, the canvas of a poem is in the reader’s mind. It seems impossible. We’re rendering the complexity of the human condition in a form that would seem wholly unsuitable to the task: symbols on a page.

What’s amazing is not that words fail; it’s that sometimes they don’t. The human brain, through some evolutionary mystery or miracle, responds to sensory language the same way it responds to the physical world. You read sandpaper, you read scratch, you read grainy, and the same part of your brain lights up as if your fingers had trailed across a sheet of actual sandpaper. So perhaps language isn’t so unsuitable to the task after all; our brains, it turns out, are built for poetry.

Of course, the work of the image in a poem goes beyond evoking a picture (or taste or song or smell) in the reader’s mind. We want our poems to mean. To convey something of our experience in the world in hopes that someone else might connect with it. My friend Todd Kaneko says poems always mean at least two things. This, too, is tied to the image. Doty, again: “Perception is simultaneous and layered, and to single out any aspect of it for naming is to turn your attention away from myriad other things, those braiding elements of the sensorium—that continuous, complex response to things perpetually delivered by the senses.”

In a Tin House Summer Workshop craft talk from 2015, Natalie Diaz says, “An image is more than what we show our readers—it is story, it is history, it is emotion.” She uses the example of an apple. To put an apple in a poem is to bring to that poem all of our cultural associations with the apple. Eve and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Temptation. Snow White and the poisoned apple. Not to mention a reader’s personal associations with the fruit: a stack of apples in the local grocery store, bins of them at a farmers’ market. Here in Michigan, where I’m writing this essay, the apple is a staple of the state’s industry. I’m thinking, too, about the tiny tart apples on the tree in the yard of the farm where I grew up in Alabama. An apple is not only an apple; it is all these apples. The image is layered, complex, possibly contradictory. (That contradiction is not incidental to a poem; it’s essential. The poem, perhaps more than most forms of art, is especially suited for exploring the contradictions inherent in how we experience the world.)

Consider another image: the white plastic grocery bag. What does that call to mind? Convenience. Disposability. Litter. Waste. American capitalism. Consumer culture. Temporariness. A clumsy, overwrought metaphor in American Beauty, a movie that has not aged well since winning Best Picture in 2000. To put a white plastic grocery bag in a poem, then, does more than create a picture in the mind of a reader; it evokes a range of meaningful associations: layered, complex, contradictory.

With all that in mind, then, read “Poem About Water,” by sam sax, from the terrific collection bury it. The poem is here in its entirety:

i get it. your body is blah blah blah percent water. oceans levitate, clouds urinate on the ground that grows our food. this is considered a miracle – this is a problem of language. i could go on for days with facts about the ocean and it will always sound like i’m talking about love. i could say: no man has ever seen its deepest trenches, we know less about its floor than the stars, if you could go deep enough all your softest organs will be forced out of your mouth. you can be swallowed alive and no one will hear a sound. last summer three boys drowned in the sound and no one remembers their names, they came up white and soft as plastic grocery bags. i guess you could call that love. you’d be wrong.

There’s much to say about this poem. It is an ars poetica, a poem about the nature of poetry, a poem about image and metaphor: about how the language of one particular maps onto the language of another. In this case, water and love. And then we get those grocery bags at the end! At its most basic level, the simile is a fresh way to describe something pale. But of course it’s more than that. The image paints a picture, as they say, but it also does so much work to make meaning. All those associations about white plastic grocery bags enter this poem; they shape how we feel about the boys, about how society doesn’t remember their names, about death, about loss, about water, about love. The poem is already brilliant, darkly funny, provocative; this startling image makes it all the more so.

The theory that I’ve been building to here is this: prose poems in particular need that startling image. Without it, a prose poem is not a prose poem at all—merely prose.

* * *

Back to the OED. The verb to startle is “to cause (a person or animal) to undergo a sudden involuntary movement of the body, through surprise, alarm, etc.; to surprise greatly.” As Robert Frost famously says, “No surprise in the writer, no surprise in the reader.” Part of the poetic impulse is to startle. The OED also notes that as an intransitive verb, “startle” once was “chiefly used of cows rushing wildly about a field in the grip of some irritation (stinging insects, burning sun, etc.).” It does not specifically list prose poems as a potential cause of this state, but perhaps it could have.

In his introduction to the anthology Great American Prose Poems, David Lehman traces the form’s origin to Baudelaire and the French surrealists. No surprise, then, that prose poems so often lean toward the strange, the unusual, the ludicrous. If you’re not simultaneously fighting against and borrowing from the traditional hallmarks of prose—narrative or the straightforward providing of information—you’re not writing a poem. The project of poetry is to disrupt the reader’s perceptions, to interrupt their lives, to build a piece of art that says, here, step out of time with me for a moment and experience this new thing I’ve made for you. Lineated poetry has the built-in mechanism of the line to achieve this disruption—the word verse has its roots in the act of turning to begin another line as when plowing a field. Lineated poems look like poems. They signal their disruption by their appearance on a page even before you begin reading.

Prose poems do not have this visual clue to their objective. They appear innocent enough: inviting paragraphs, digestible bits of prose—how hard could it be? I know that when I write prose poems, it’s often because I have become bored with my own approach to the line, when I am tired of the obvious artifice of enjambment and end-stop. Lehman writes in that introduction, “Writing in prose you give up much, but you gain in relaxation, in the possibilities of humor and incongruity, in narrative compression, and in the feeling of escape or release from tradition or expectation.” For me, the key word in that sentence is incongruity. If I can’t surprise my reader with my line breaks, what tool is most readily at my disposal? The startling image.

Lehman’s anthology was published in 2003, and part of its project was to make the case for the prose poem, to argue for its right to exist as a form. Such a case hardly needs to be made anymore; prose poems are everywhere. It’s rarer to find a collection or an issue of a journal without any than with at least a handful. Which means, certainly, there are plenty of mediocre prose poems out there, bland little paragraphs that are pleasantly digestible and immediately forgettable. What are they missing? Often, it’s the startling image that is absent. The out-of-nowhere simile or description that puzzles the reader and enlarges the poem; that connects the world of the poem to the world we physically inhabit; that at once vividly illustrates a scene or a moment and challenges us to see it in a new way.

By way of example, we can look toward DMQ Review’s own most recent issue, the prose poem issue. The poems in this issue both describe and evoke. Nin Andrews’ “Evening Drinks,” for instance, is full of sensory details that precisely render a girl listening in on her father’s intimate experience. The scene is rendered in such detail—and then we get this moment: “She imagined they were tiny people inside a paperweight.” Such a seemingly simple sentence enlarges the poem; it brings in all our associations about paperweights and snow globes—American nostalgia, witness, containment, safety, so much more.

The examples continue throughout the issue. Go poem by poem and look at how they rely on images to create meaning. M.A. Scott’s “Pink Magic” explodes conventional associations with the titular color, as in this sentence: “Anoint a pink candle with your personal concerns, then take the wick into your mouth like a sword.” That leap from candle to wick to sword—that’s what I come to poetry for. Vy Anh Tran’s “America,” closes with this: “and, of course, whatever colors the American flag are.” You could call this an anti-image: a deliberate blurring of the visual of the flag. The reader supplies the colors the poem refuses to name. The flag is such a common image, with such obvious associations, and Tran gets to have it both ways: bring those associations to mind and fight against them, all one phrase. I could go poem by poem through this issue and find such examples: the images that elevate the poems.

* * *

If there’s a call to action here, a takeaway from this essay, it’s this: don’t settle for the ordinary image. Stretch yourself. Reach for the strange, the disruptive, the meaningful. Let your images help you make meaning. Lean into the weird and the surreal and the surprising. Use your images to fight against narrative and straightforwardness. Use them to startle, in other words.

In Paul Hetherington and Cassandra Atherton’s book Prose Poetry: An Introduction, there’s a chapter on imagery that begins by comparing the prose poem to a photograph, both in its most common shape and in its snapshotness: “many prose poems rely on providing a mere fragment or momentary evocation of a scene or set of circumstances.” The authors then quote Susan Sontag on photography and poetry, both of which are “wrenching things from their context (to see them in a fresh way), bringing things together elliptically.”

Seeing things in a fresh way—that’s it exactly. That’s why we write poems, and it’s most certainly why we read them. I mentioned earlier that I often turn to the prose poem when I am bored with my own lineated verse. Dropping the obvious artifice of the line forces me to see the nature of the poem in a new way, to find a new path to disruption and surprise. As Lehman suggests, it engenders a playfulness that is essential to creation, exploration, discovery.

How many times have you heard a poet or reader of poetry talk about the pleasure in coming across a new way of seeing the world? In language that immerses you in an experience, that offers access to someone else’s distinct perception, that challenges your expectations? To put such an image on a page and offer it to the world—to startle and to be ourselves startled—well, that’s the very heart of why we write.

Amorak Huey’s fourth book of poems is Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy (Sundress Publications, 2021). Co-author with W. Todd Kaneko of the textbook Poetry: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology (Bloomsbury, 2018) and the chapbook Slash/Slash (Diode, 2021), Huey teaches writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan.